Lighting approximations

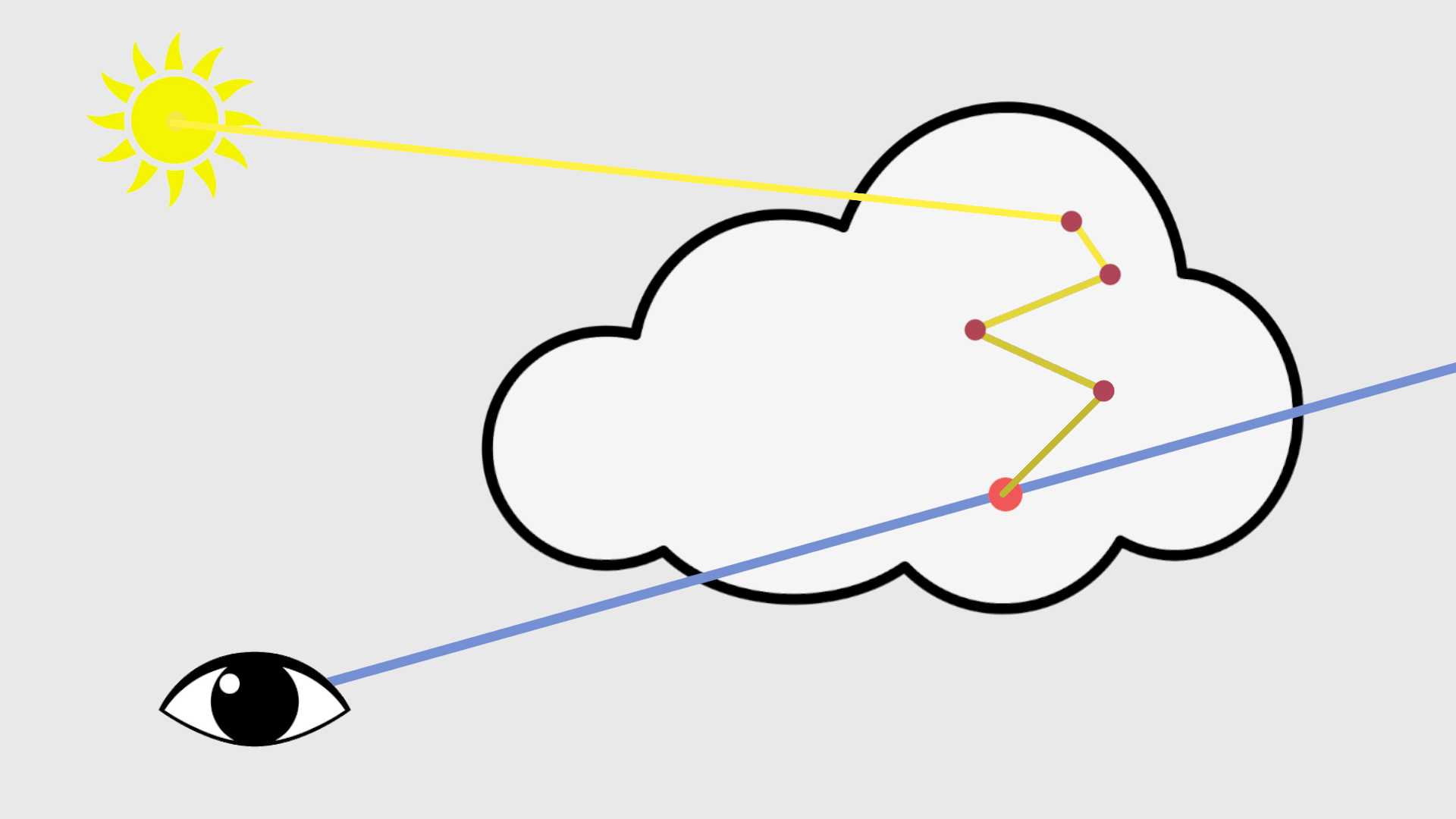

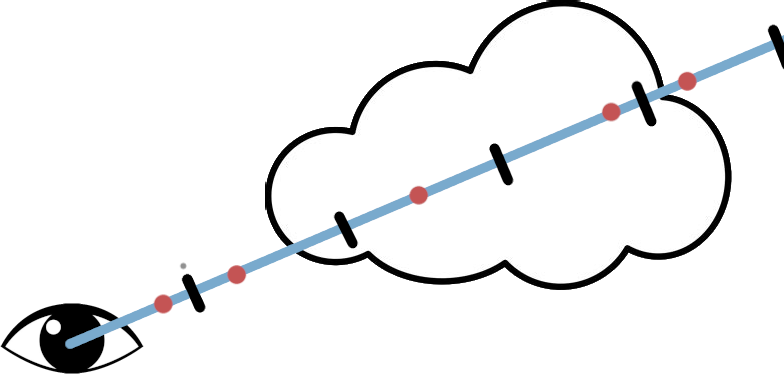

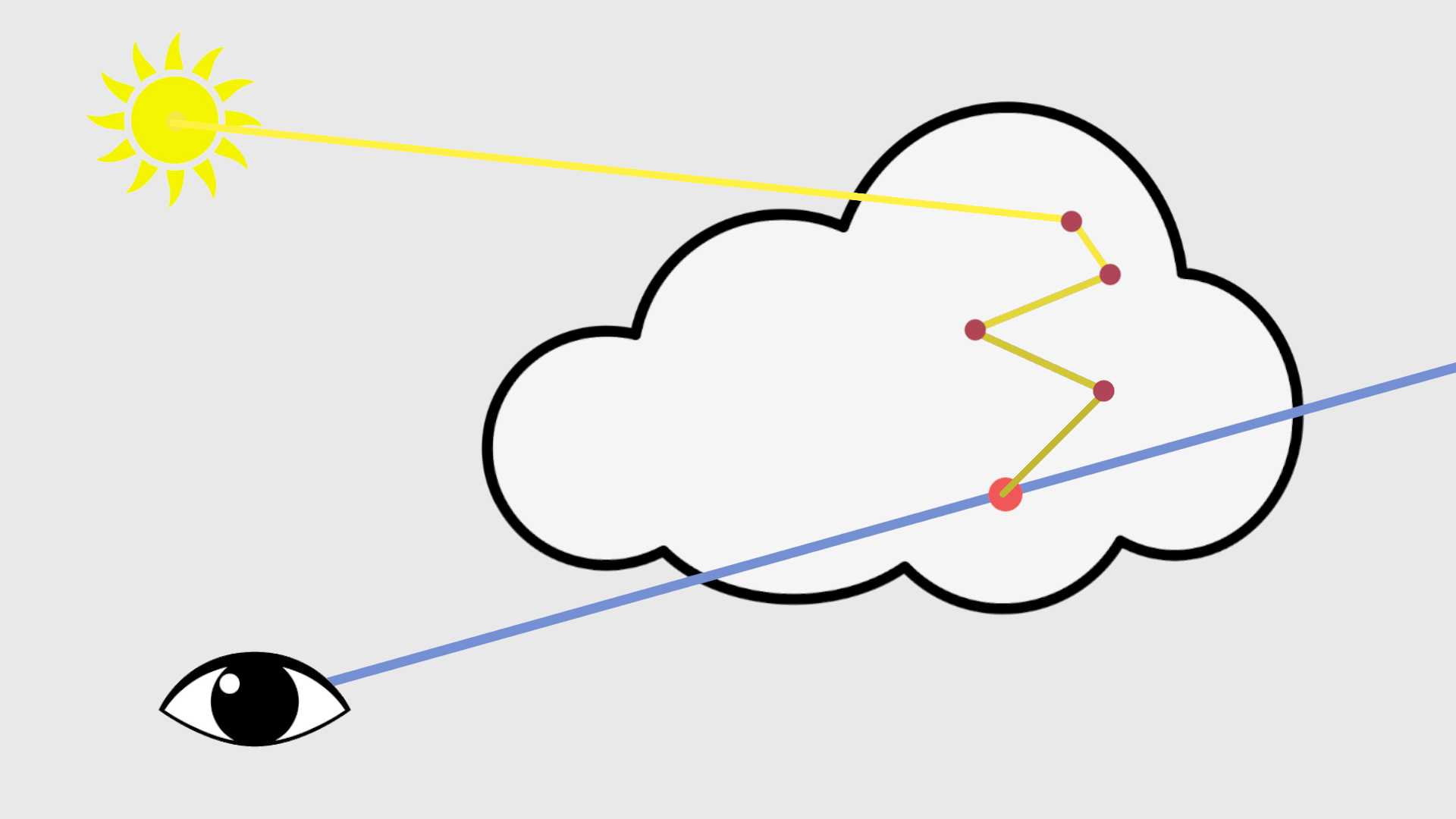

The lighting in real clouds is not as simple as a straight line towards the sun/light

source.

In fact, there are more incoming sources and light bounces around the inside of the

cloud.

Simulating this would be very expensive, but there are some good approximations that

give us a

more realistic look.

Phase

An important factor in lighting volumes is that they do not scatter light evenly in all

directions;

in fact, they scatter light significantly more forward.

This causes clouds between you and the sun to be way brighter than when looking at

clouds

opposite to the sun.

This factor can be calculated by the Henyey-Greenstein function.

It takes an eccentricity factor; lower values mean the light is more biased towards the

incoming

light

direction.

// Phase function

float HenyeyGreensteinPhase(float inCosAngle /*the dot product difference between look and light direction*/, float inG /*The eccentricity*/)

{

float num = 1.0 - inG * inG;

float denom = 1.0 + inG * inG - 2.0 * inG * inCosAngle;

float rsqrt_denom = rsqrt(denom);

return num * rsqrt_denom * rsqrt_denom * rsqrt_denom * (1.0 / (4.0 * PI));

}

This can be directly applied to the lighting.

light += CalculateLighting()

* HenyeyGreensteinPhase(dot(rayDir, LIGHT_DIRECTION), g /*0.2*/) <changed>

* transmissance

* density

* stepSize;

Ambient lighting

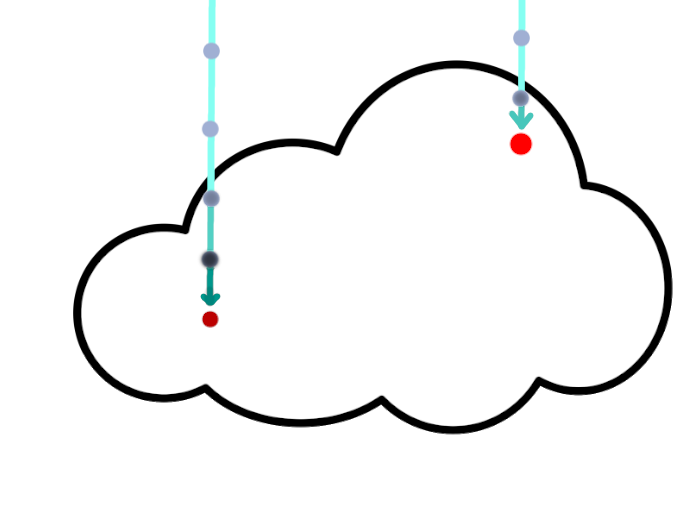

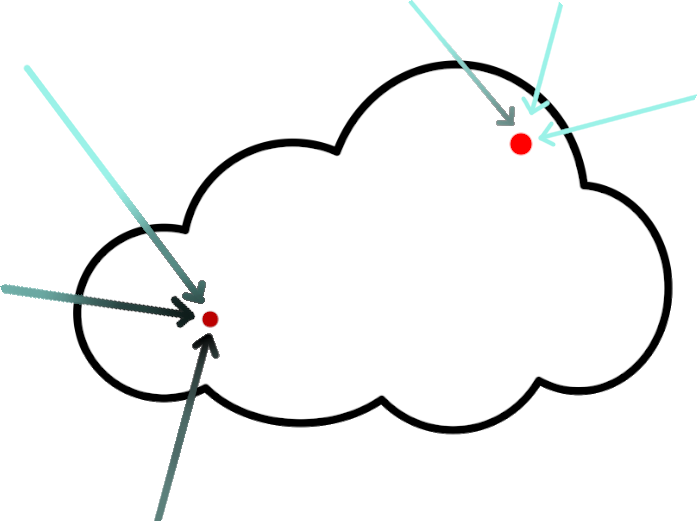

An important factor in lighting clouds is ambient light that comes from the sky.

This causes clouds to be more lit with the color of the sky when not directly

illuminated by the

sun, and adds more realistic shadowing since covered parts get less sunlight.

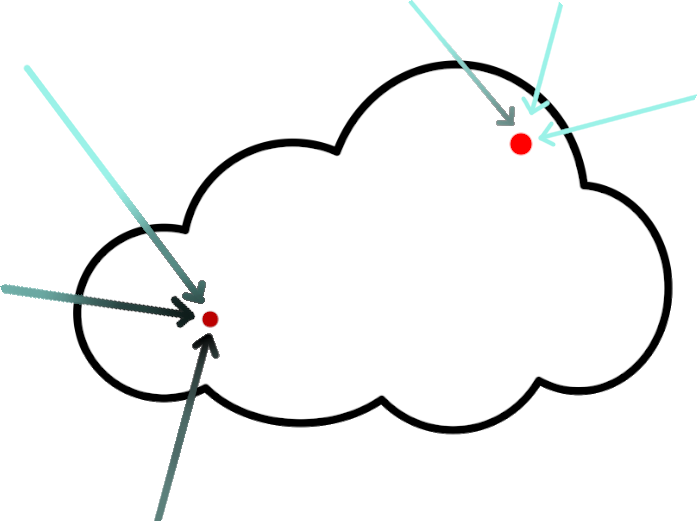

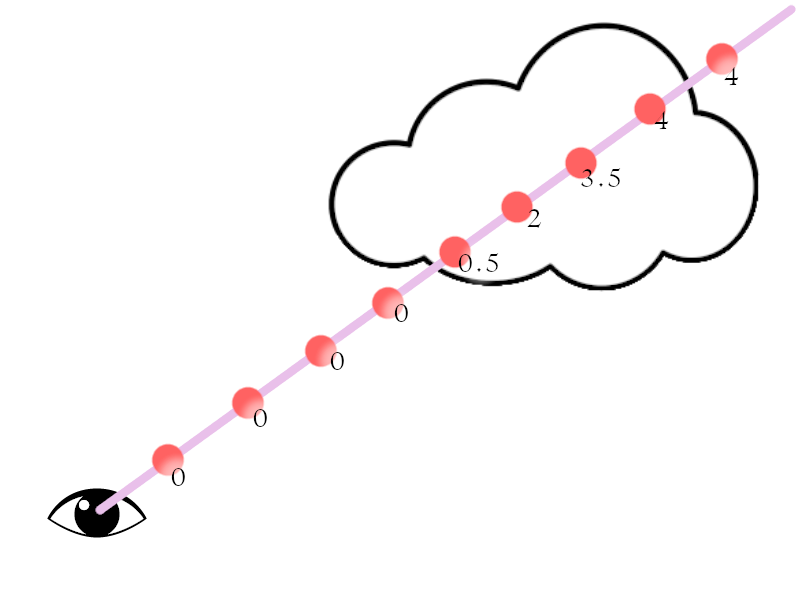

Ambient light coming from all directions, deeper and lower parts

are more

shadowed

It would be way too expensive or noisy to calculate this by shooting actual rays in

"random"

directions.

So instead, we use an approximation.

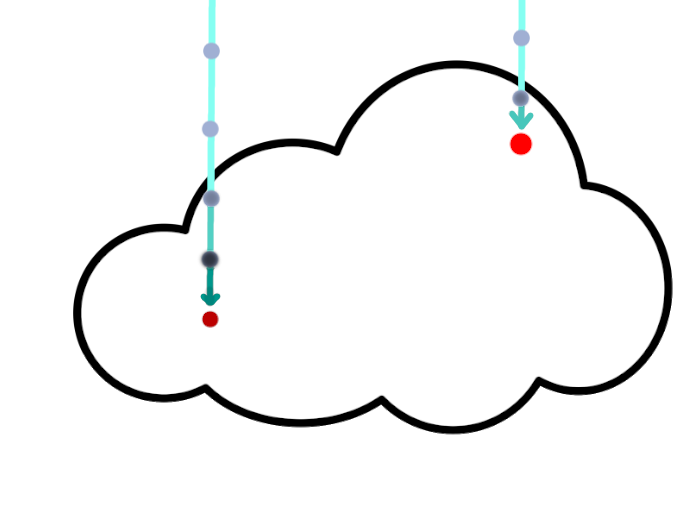

We can assume that most of the ambient light will come from the sky above since that is

the

brightest part of the sky.

Keeping this in mind, we can combine the entire sky into one upwards ray.

What we do is first combine the sky into one light value/color by integrating the sky

hemisphere once.

I won't go over how to do this, but it can be done by either random sampling or

spherical

harmonics.

Alternatively, you can just pick a color that resembles your sky.

To approximate shadowing of the rays, we shoot a ray upwards.

Since this light is not directional, it is not affected by either phase or sun

direction.

That means this upwards ray can be precalculated for a static grid, and since this data

is

already blurry by itself, it can be stored in a lower resolution grid.

Single ray approximation

To combine this all together, we weight the ambient lighting by not only this ray but

also by

how far

into the cloud the sample is.

This is because the edges of the cloud receive more ambient light from around than the

center of

the

cloud does. We can reuse the profile for this.

for(int i = 0; i < NUM_SAMPLES; i++) { // sample loop

...

// Ambient approximation

sampleLight +=

saturate(pow(profile, 0.5) // here we use a slightly modified profile to change the falloff of ambient light at edges,

// this could also be a remapped distance field to the edge of the cloud, we get into this later

* exp(-GetSummedAmbientDensity(samplePosition))) // Summed density of the upwards ray, this can be a precalculated texture sample or an actual march.

* (AMBIENT_LIGHT); // Light from the sky, could be a single color or a preintegrated sky light

...

totalLight += sampleLight * transmissance * sampleDensity * stepSize;

...

}

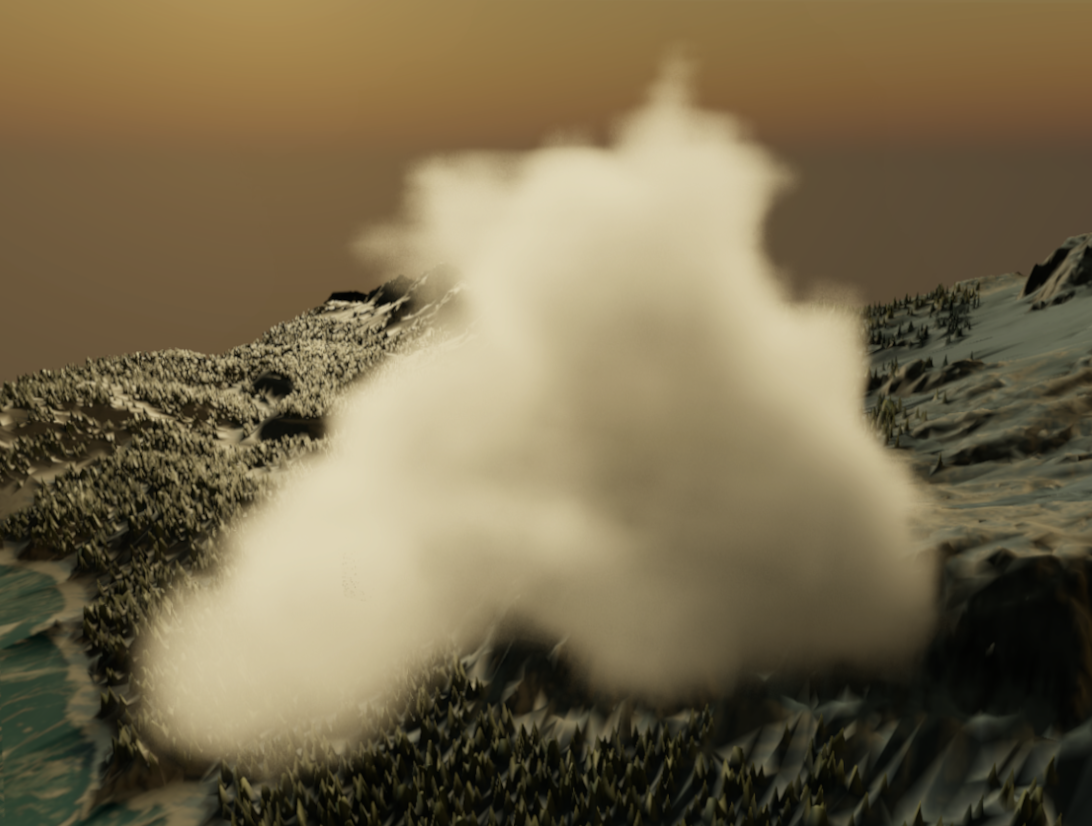

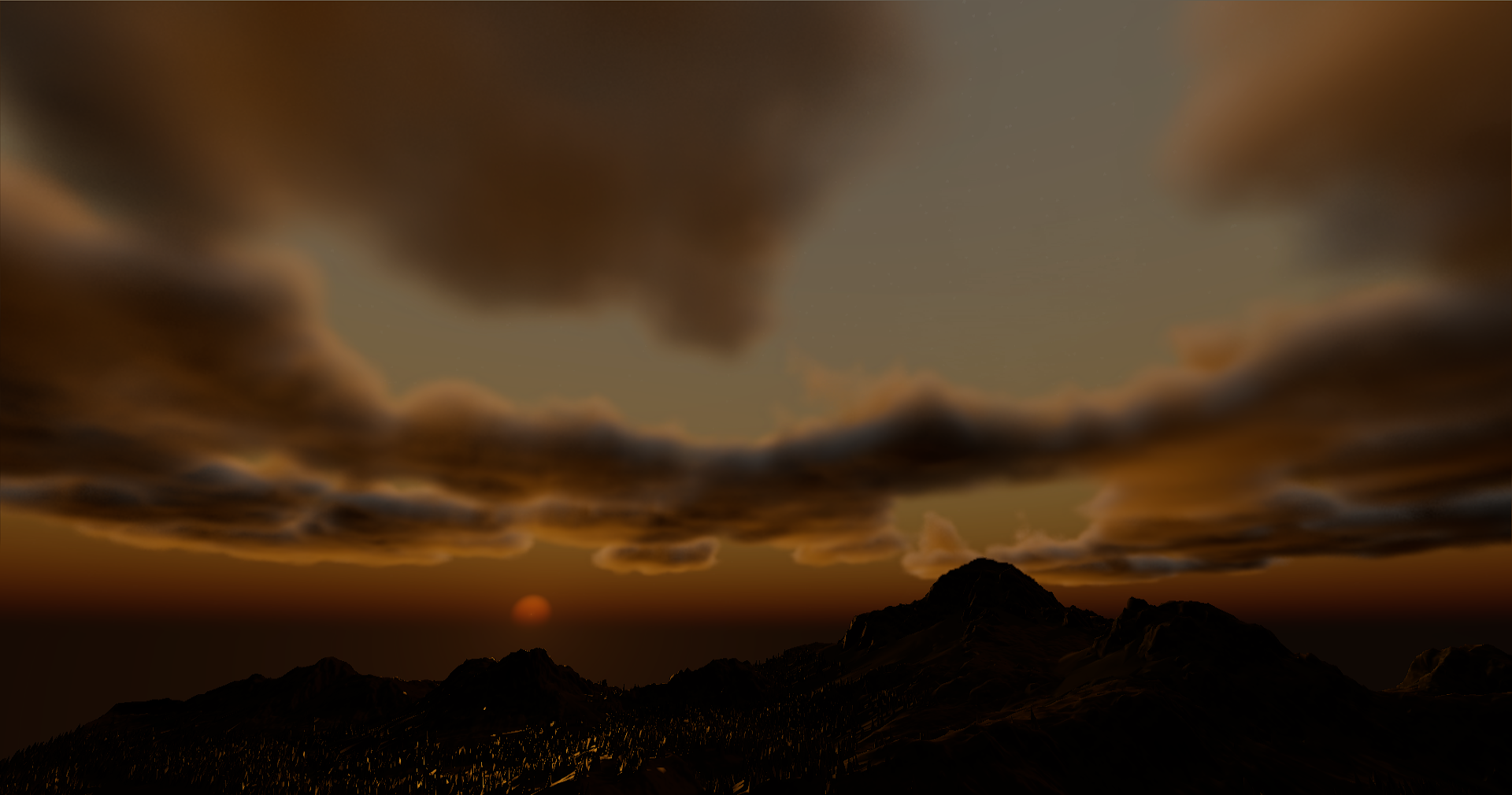

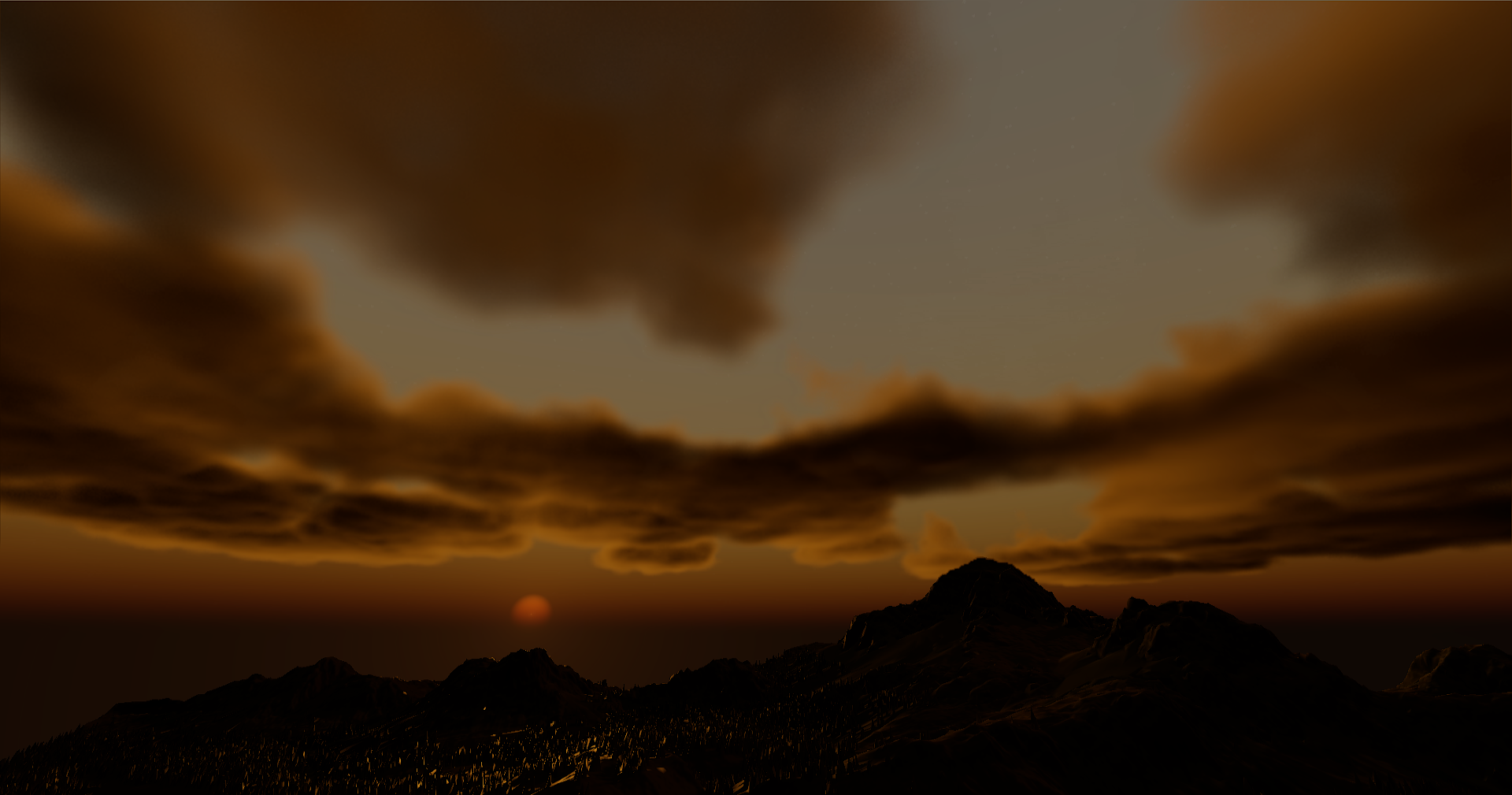

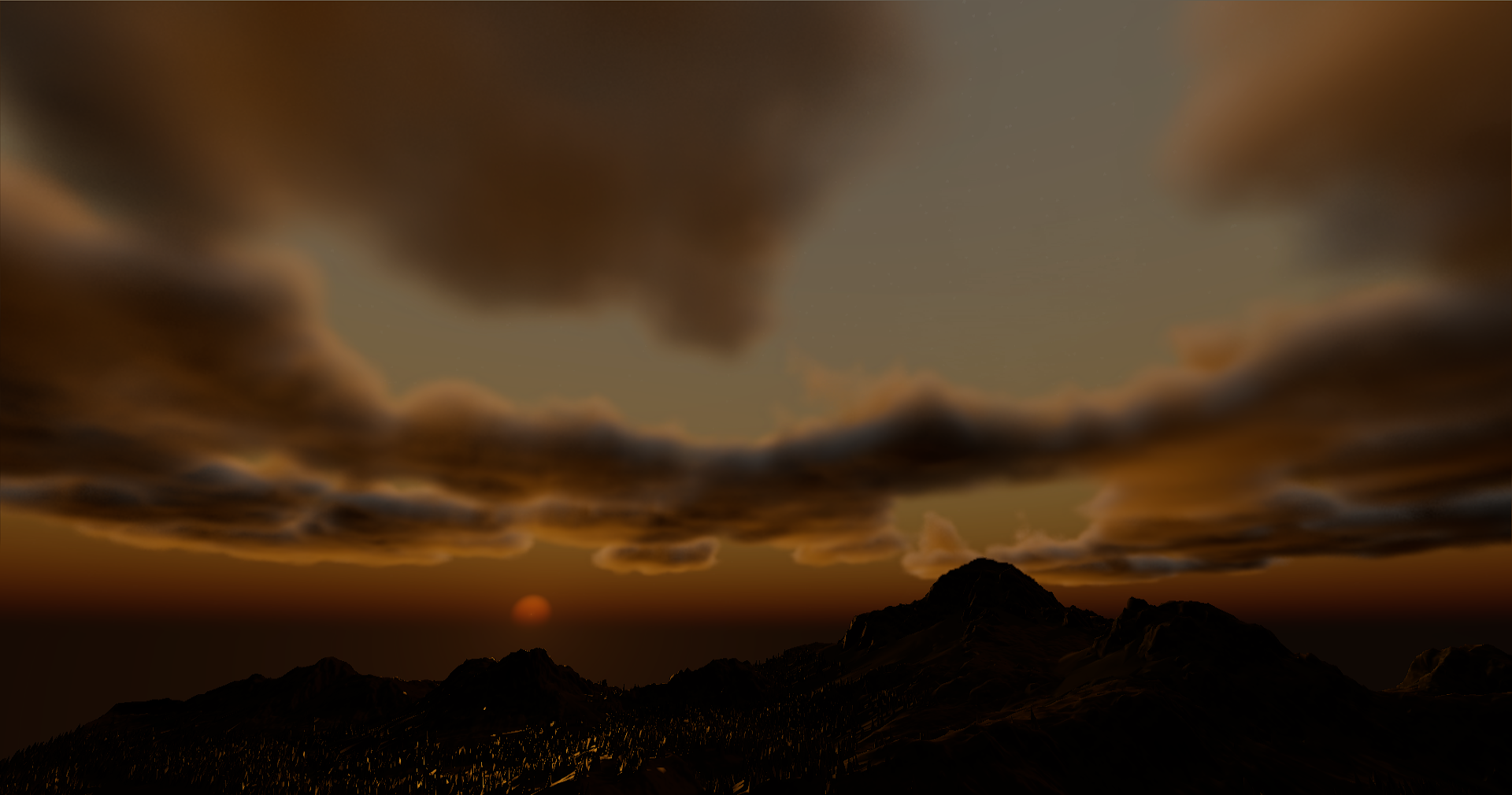

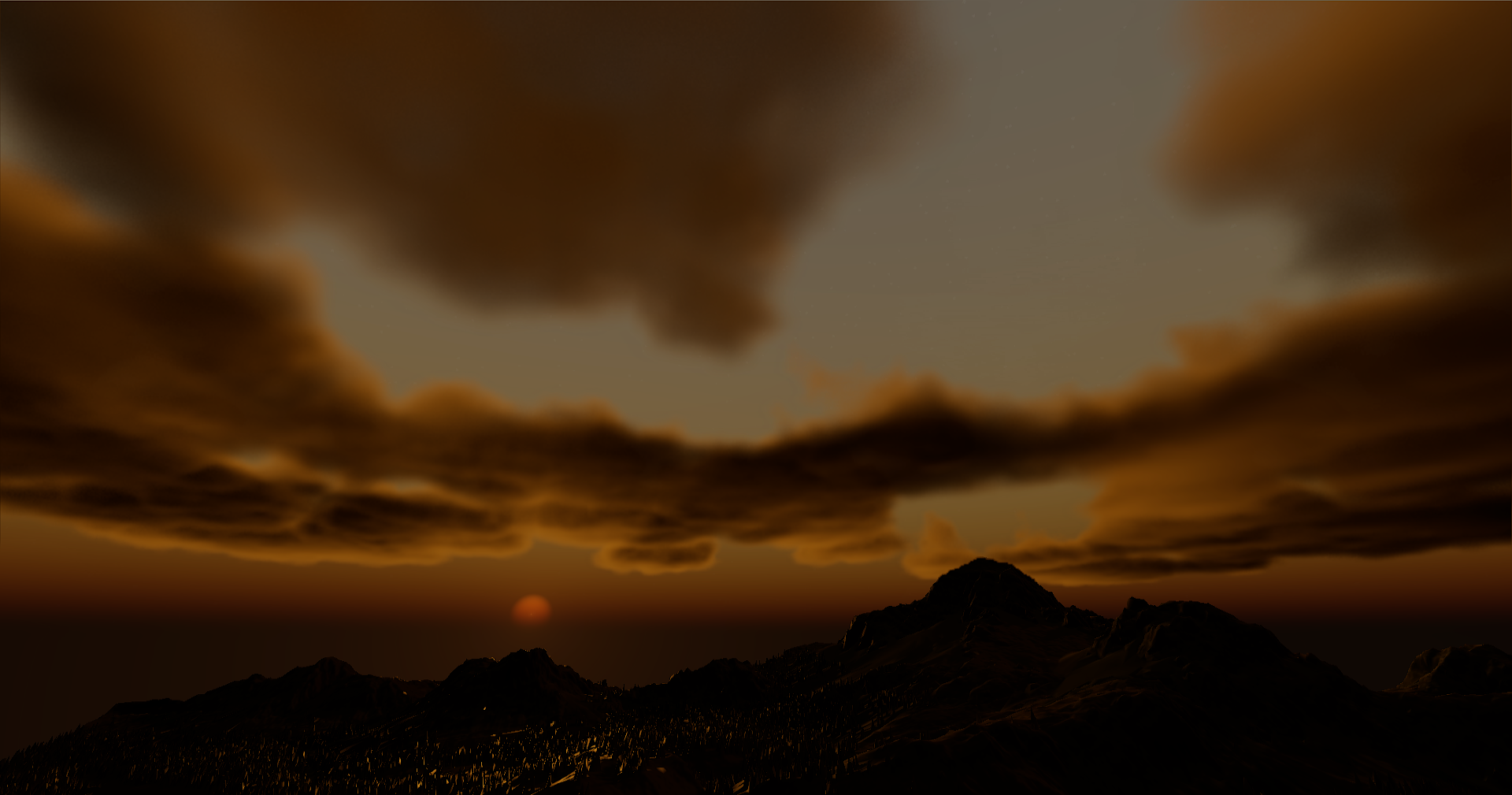

Comparison, you see mainly that the parts away from the sun are not

unrealistically dark anymore

and shadowed parts (the underside) stay shadowed

No Ambient

With Ambient

Multiple in-scattering

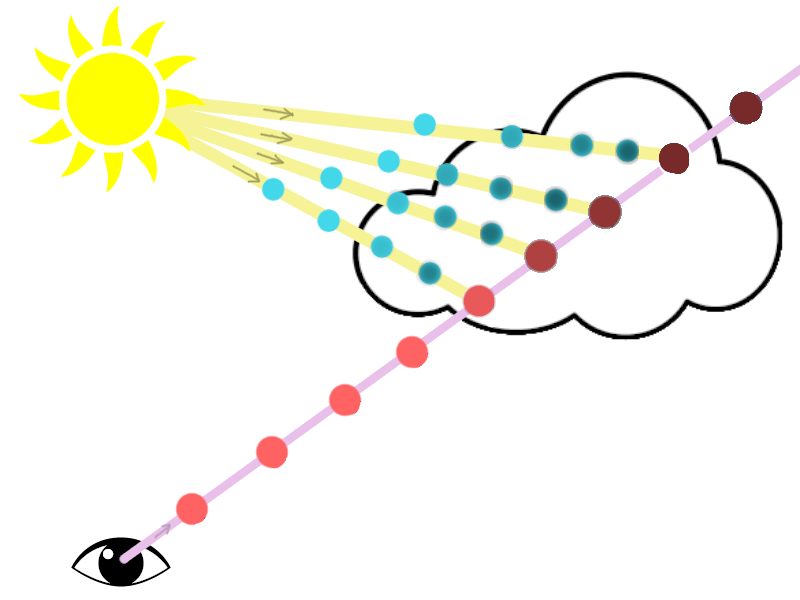

Clouds do not only receive sunlight directly from the source.

Light also scatters around the inside of the clouds and can hit our sample indirectly.

This would also be too expensive to calculate, but we can approximate the results.

The main effect that results from multiple scattering is that the inner parts of the

clouds

become brighter.

This is because the inner parts have more cloud around them to scatter light from.

We also have to take into account the phase (so the angle to the sun) here since the

scattering

is

still biased towards the light direction.

The approximation is not too accurate but gives a good-looking result and is very cheap.

This is not too bad since the effect of direct lighting is significantly stronger.

float InScatteringApprox(float _baseDimensionalProfile, float _sun_dot, float _accumulatedDensity)

{

// This accounts for the phase // how far inside the cloud, (should also use a distance field but this is fine for now)

return exp(-_accumulatedDensity * Remap(_sun_dot, 0.0, 0.9, 0.25, Remap(_baseDimensionalProfile, 1.0, 0.0, 0.05, 0.25)));

}

// In the march loop

...

// March towards the sun adding up density.

float inSunLightDensity = DirectLightMarch(); <changed>

// // not using uprezzed profile

float lightVolume = InScatteringApprox(1 - baseProfile, sunDot, inSunLightDensity); <changed>

sampleLight +=

lightVolume <changed>

* HenyeyGreensteinPhase(dot(rayDir, LIGHT_DIRECTION), g/)

* SUN_LIGHT;

...

totalLight += sampleLight * transmissance * sampleDensity * stepSize;

...

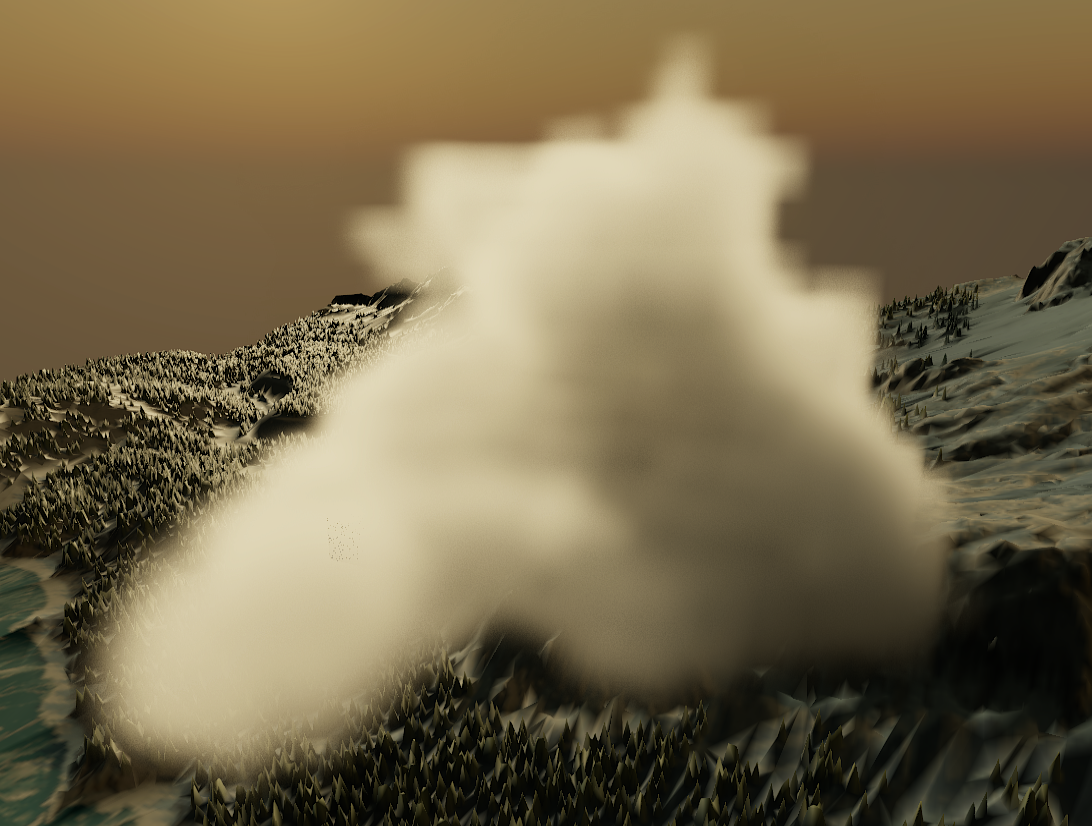

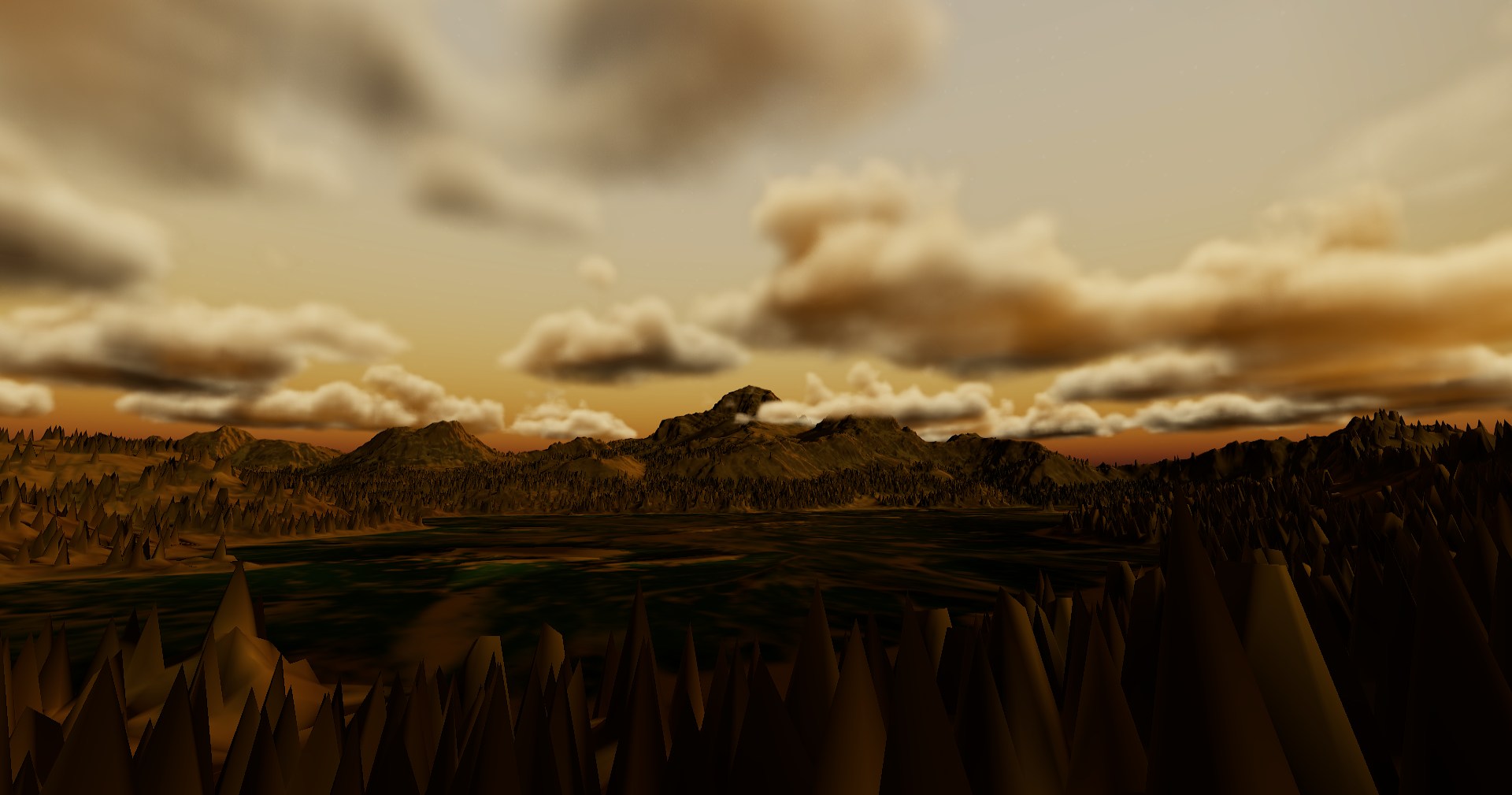

Comparison, you see that the inner parts of the cloud are

significantly

brighter.

You can also see inner edges in the middle of the cloud be slightly darker adding

detail.

No Scattering

With Scattering

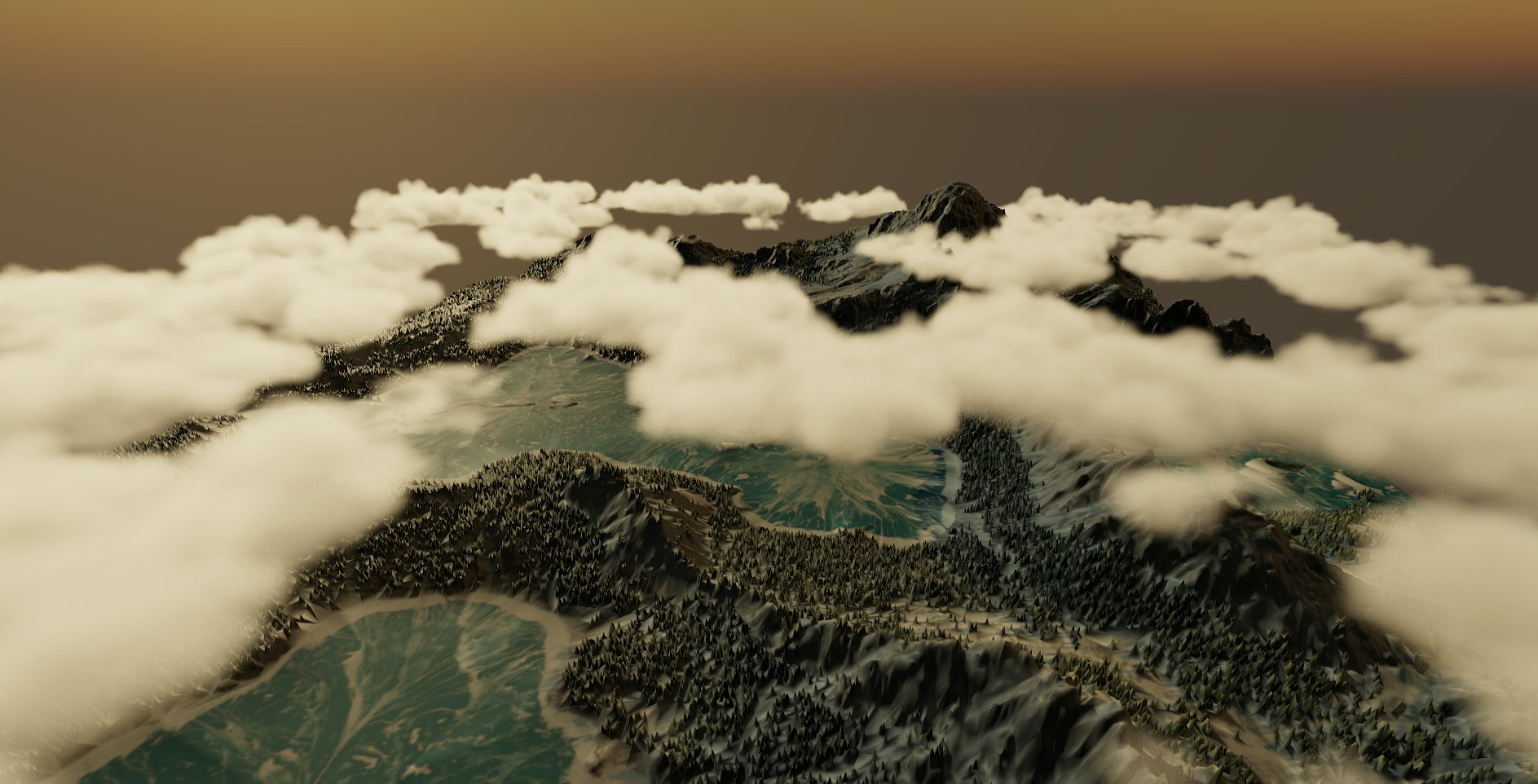

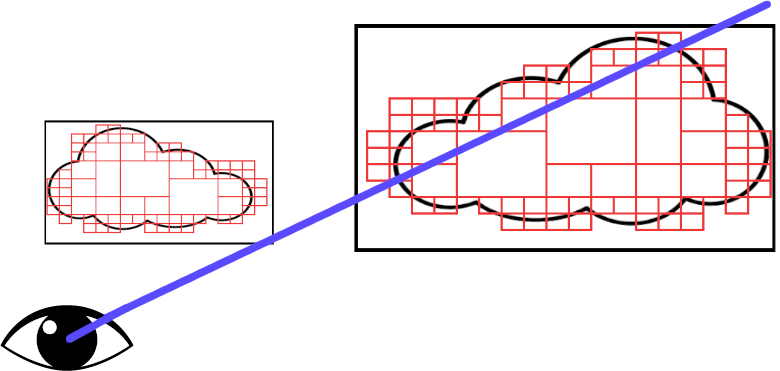

For every step along the Ray we sample the density of the volume and accumulate the

total along

the ray.

For every step along the Ray we sample the density of the volume and accumulate the

total along

the ray.

For now, we'll calculate our density using the distance from a sphere.

For now, we'll calculate our density using the distance from a sphere.

This has a lot of benefits in memory usage, allowing you to store significantly more

detailed

clouds.

This has a lot of benefits in memory usage, allowing you to store significantly more

detailed

clouds.